Importance of microscopy for cell biologists in general and spermatologists specifically

Part 1: Basic and historical aspects: do spermatologists/andrologists use the microscope correctly?

This is the first of a three-part series on the importance of microscopy particularly for those who investigate sperm biology. Why is this so important? In order to study sperm motility, sperm structure or sperm function making use of image analysis (e.g. SCA), the correct settings for all the optical components must be perfect. The image must be sharply focused and the background illumination must be even. Most of the readers of this blog will wonder: But I do everything correctly every day and accordingly… so that, why do I need to read this?

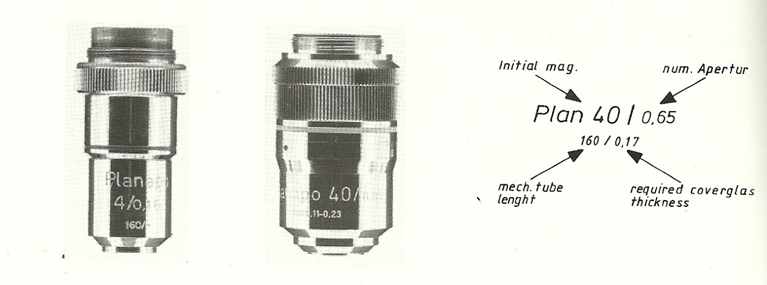

I was fortunate to visit some 40 sperm/andrology laboratories in about 27 countries worldwide in the past six years. It may surprise you that in more than 80% of these laboratories microscopes were not properly and correctly used. The implication is that you may miss crucial details while observing sperm and even false images. There are basically just two questions that I ask to establish if users have a basic understanding of microscopy. Firstly, what the inscriptions on the objective lens mean? Most spermatologists will only get the magnification of that lens correct but what about NA, Plan Apo, Ph1, 0.17 etc.? (Fig. 1) Secondly, what is Critical and Köhler illumination and how do you set it correctly in a microscope? Many hear these terms for the first time when I ask the question (basically focusing the light source perfectly on the object and obtain an even background illumination). A good knowledge and understanding of the above aspects are essential to use your microscope correctly and I will explain these in detail in next Part 2. I will then provide a stepwise checklist how to do it perfectly in any microscope model. I suggest that in the meantime you check this out if you do not already know this.

Fig. 1: Lens inscriptions and what they refer to. Before microscope blog 2 will be published – try and decipher yourself what all of this means.

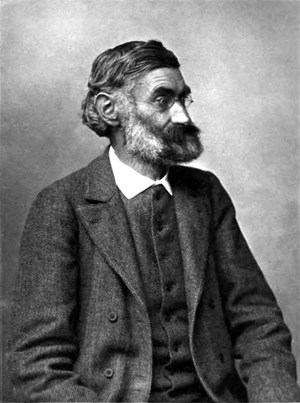

Fig. 2: Ernst Abbe, who must be considered the father of optical microscopy. For the first time in Jena, Germany, and with Carl Zeiss, it was possible to construct lenses and microscopes on a scientific basis and not make developments by pure chance. He paved the way for scientists such as Retzius to make such amazing descriptions of spermatozoa.

Part 3 will deal with specialized microscopic techniques such as phase contrast, Nomarski differential interference microscopy, fluorescence, laser confocal microscopy and even the basics of scanning and transmission electron microscopy. All these facets help us to visualize the spermatozoon optimally and chances for correct automatic image analysis better.

I want to end off the first blog asking how was it possible that amazing scientists such as Gustav Retzius could study sperm morphology of some 400 species in such great detail in just 5 years (1904 – 1909)? Ernst Abbe (Fig. 2) laid the foundations for microscopy used up to today. He already established in 1897 that the maximum Numerical Aperture (NA) that can be obtained using a light microscope was 1.4. The point is that if you know the NA you can determine the smallest distance you can distinguish between two points (resolution). Under ideal conditions in Retzius time they used microscopes that had NA of 1.3 to 1.4 for a x100 objective lens. Today most research microscopes are equipped with a NA of 1.25 for the x100 lens. They furthermore used day light and a mirror system (Fig. 3) and the quality of day light in terms of reflecting true colour is superior to tungsten light (LED now used in most modern microscopes is a great improvement above tungsten or halogen). Lastly, they used ingenious preparation techniques which most of us only use for electron microscopy.

The three microscopes in Fig. 3 are from my own collection at home, and the middle one has a NA of 1.3 and dates back to 1899. Retzius seems to have used a very similar microscope in 1904 and in his notes, remarks: I could not wait for the first sunlight in the morning (mirror catching sun rays) to study the sperm of all these interesting animals. But he used the microscope under optimal conditions and preparation techniques.

Fig. 3: Three microscopes from Gerhard van der Horst’s collection. The two on the left date back to about 1897 and 1899 and used mirrors to reflect the sun rays as light and the one on the right some of the first using an electric bulb (1947). They used Abbe optics.

PS: The microscope blogs will be alternated with interesting blogs such as studying sperm of Tankwa goats in the arid Karoo of South Africa and the Unique Primate Unit where major research has been done on HIV and also spermatozoa of vervet/green monkeys and Rhesus monkeys and baboons.

To be continue…

Gerhard van der Horst (PhD, PhD)

Senior Consultant

MICROPTIC S.L.

Leave A Comment